RICE, REFUGEES, AND ROOFTOPS: A Comprehensive History of Air America, 1959-1974.

by Harry Richard Casterlin

- VOLUME I - GENESIS: The Air America, Inc., Helicopter Program in Laos, 1959 to May 1962

- VOLUME II - THE CROTCH: 1960-1962: An Overseas Tour in the U.S. Marine Corps Leading to the Decision to Join Air America

- VOLUME III - FEET WET: 1962 and the Year of the Tiger

- VOLUME IV - 1963: Resumption of the Second Indochina War in Laos

- VOLUME V - 1964: Escalation and Military SARs

- VOLUME VI - 1965: A Tedious Year

- VOLUME VII - 1966: A Time of War and Peace

- VOLUME VIII - 1967: More of the Same

- VOLUME IX - 1968: Devastating Losses

- VOLUME X - 1969: The First Plain of Jars

- VOLUME XI - 1970: Continue to March

- VOLUME XII - 1971: The Second and Final Plain of Jars

- VOLUME XIII - 1972: A New and Invigorating Program

- VOLUME XIV - 1973: Holding on During Negotiations

- VOLUME XV - 1974: Out of Business in Laos

- Related Resources

After the Vietnam War ended in 1975, the Air America Company became famous for its service supporting the Central Intelligence Agency's Secret War in Laos. While providing Search and Rescue services for downed military pilots in Laos, they flew combat missions only in Laos. They also provided non-combat air support in Thailand, Laos, Vietnam, and Cambodia, and supported the Royal Lao Army and the Meo Army of General Vang Pao and other ethnic groups. Over time, and with the publishing of questionably sourced studies, Air America's service also became mired in myth, misinformation, and a notoriety that was inaccurate and a disservice to the American and third country nationals who served with Air America during the Vietnam War.

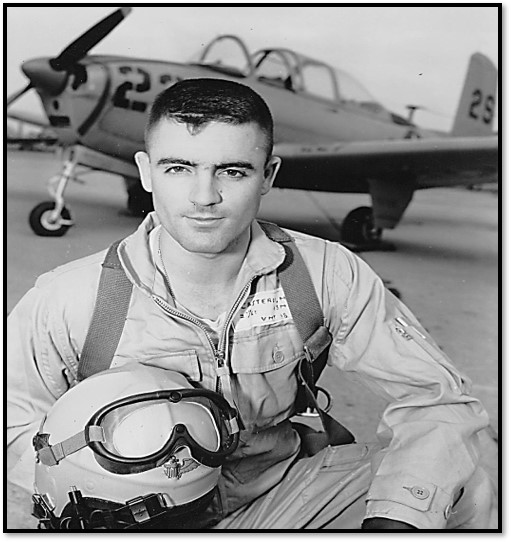

Harry "Dick" Casterlin was a civilian helicopter pilot with Air America from September 1962 to June 1974, flying Sikorsky H-34, S-58T and Bell 204/205 helicopters. After the war, Casterlin dedicated his life to researching and writing the definitive history of Air America, Inc., and the Company's service in Southeast Asia during the war. Of particular significance are the first-hand accounts by Casterlin, and many of the men he flew with, of specific suspense-filled missions. He also illustrates the negative impacts of the decisions by the Top Brass in distant Washington, DC, in contrast with the actual situation and timely needs of "boots in the air" in Laos.

Dick Casterlin's 15-volume work presented here in its entirety is, by far, the most complete and comprehensive history of Air America ever written. It is an invaluable source on the Secret War in Laos and the service of Air America throughout Southeast Asia from their earliest operation in 1959 to the end of Casterlin's service in 1974.

- VOLUME I - GENESIS: The Air America, Inc., Helicopter Program in Laos, 1959 to May 1962

War cannot be described as merely a series of incidents compressed into a specific period of time. One must understand the cultures, geography, and history of a region and its peoples in order to fully appreciate the factions who are at war, and why they behave as they do. To create a foundation for later books, the first book involves many diverse characters. Covering the period from 1959 to May 1962, it traces the inception of the Air America helicopter operation in Laos with four underpowered Sikorsky machines and grossly inexperienced helicopter pilots. Later, when Laos looked like it was going to become a communist wasteland, a United States Government-sanctioned HUS-1 helicopter Madriver program was formed in Udorn, Thailand, to support the Royal Lao Army's dismal efforts.

There are many facets contained in the book's content: Marine Corps involvement developing a camp to support crews and large numbers of U.S. Marine HUS-1 helicopters, obtaining temporary military personnel from the three major services, flying combat missions in Laos, eventually turning the operation over to Air America, and hiring bona fide civilians on a one-on-one basis to support and fly missions with Meo tribesmen, who were willing to fight a hated enemy to preserve their homeland.

This first volume concludes in 1962 with Lao troops abandoning a large government base at Nam Tha, located in the northwest corner of Military Region One, and the potential impact of this on the Kingdom of Laos.

- VOLUME II - THE CROTCH: 1960-1962: An Overseas Tour in the U.S. Marine Corps Leading to the Decision to Join Air America

Saturated with youthful patriotism during the World War Two years, the Author enlists in the United States Marine Corps in college, and undergoes training for service in Southeast Asia as a helicopter pilot. Much of this period involved carrier operations and vertical envelopment training to potentially interject a HUS-1 squadron into the South Vietnam low intensity conflict.

Because of the Lao government loss of Nam Tha, Laos, and the implications that involved questionable intentions of the communists relating to further advances toward the Thai border, we were ordered to Udorn, Thailand, under an implied war footing (called battle plan A). The Third Marine Expeditionary Unit's show of force, other support, and Thai military movement to the northeast border tended to calm the festering situation, and our sizable effort moderated to little more than another large field exercise.

Not planning to make a career of the Marine Corps, during my overseas tour, I was constantly curious about the Air America organization and its possibilities for adventure, excitement, and financial gain. I had previously made contact with Company management personnel in Hong Kong, and again in Udorn, where the Company's helicopters were staged, dispatched, and maintained.

After leaving the service in August 1962, I was hired by Air America through the Washington, D.C. office, and prepared to journey back to Southeast Asia.

(304 pages; 95 photographs, maps and diagrams.) - VOLUME III - FEET WET: 1962: A Snapping in Process

During the final three months of 1962, the Author settled into a new job with Air America, complete with numerous disappointments and pitfalls. Because the Geneva Accord protocols on Laos had been signed in July 1962, flying was much diminished when I arrived in Udorn, and then continued to dwindle to virtually nothing. The only incident worthy of note occurred when, flying at the controls of a HUS-1 as a First Officer with Captain Tom Moher in Laos, my helicopter received minor battle damage from an angry soul on the ground. The hit marked my first, but not the last, combat encounter during my almost twelve- year tour. As a questionable badge of courage, it afforded me some bragging rights in the jaded pilot group.

With little demand for our services in Laos, and too many idle, disgruntled pilots, I was not upgraded to Captain and remained a First Officer for several months at a lower base salary. Because of the stand down, we remained on tenterhooks, wondering how long the operation could continue without producing tangible work.

During the lull I was able to acquire some Thai history and assimilate Thai culture. This very pleasurable phase provided the necessary building blocks that remained throughout my long association with the Company.

(435 pages.) - VOLUME IV - 1963: Resumption of the Second Indochina War in Laos

Since we were not working in Laos, as a make work project to keep the pilot and mechanic group together, a contract was signed with the Joint U.S. Military Advisory Group in Bangkok, Thailand (JUSMAGTHAI), to fly assorted missions out of Don Muang Airport. These included trips to American sponsored Special Forces training camps throughout the southern area, and people-to-people parachute jumps in remote villages. Although not frequent, the work allowed an excellent opportunity to view part of the country. Assignments to Bangkok continued throughout much of the year.

In Laos, with tensions mounting in Military Region Two (MR-2) on the strategic Plain of Jars (PDJ) between the Neutralist forces supporting Laotian Prime Minister Souvanna Phouma and the communist enemy factions, thirteen of our bailed helicopters were withdrawn for use in Vietnam. This reduction of assets made little sense, for it left us with next to nothing to fly just when conditions looked promising for a return to the low intensity conflict.

When fighting actually commenced on the Plain of Jars in the late spring, we returned to Laos and I was upgraded to Captain. Ironically, my first trip upcountry toward the end of May in the capacity of pilot-in-command became my initial moment of truth, when an enemy machine gunner shot out my right tire.

With only a handful of helicopters left in the inventory, and far too many pilots to man them, our upcountry trips were planned for short durations of two to three days. The accumulated time was expected to constitute the total for the month. Flight time increased marginally when we received three additional helicopters in the fall.

During these trips, I stayed overnight in a rat infested hut at the refugee village of Sam Tong, overseen by Edgar ???Pop??? Buell, the Regional International Voluntary Service/U.S.Aid for Development representative. Initially the autocratic-home spun-Buell appeared to be the head man in charge of all operations. In time, I would learn a considerable amount about the Meo people and the current situation from Buell and the informative and dedicated people supporting him.

During this period of a low intensity conflict, and despite the horrible flying weather, I was able to learn and practice the basic techniques of mountain flying, with little pressure and few problems. Conditions were such that I never stopped learning.

Late in the year, with hostilities escalating in the hills overlooking enemy logistical Route-7 leading from North Vietnam to the Plain of Jars in Military Region Two, refugee evacuations commenced. Many of these missions were assigned from Long Tieng, a military sister site to the refugee center at Sam Tong. Vicious fighting produced casualties that required medical evacuations to the rudimentary Sam Tong hospital.

President John F. Kennedy's November assassination in Dallas shocked everyone. The deed lent an aura of the unknown to us in Udorn, as we wondered what the new president would do and what was next for our operation. We were further troubled when Thailand's Prime Minister Sarit died shortly afterward.

By December, we began journeying further afield to support sites that Colonel Vang Pao, the aggressive Meo civil and military leader, was adamant about recovering and holding. One of these positions was located on an elevated mountain which required developing new landing techniques. These methods reached a crescendo when I was tasked to deliver a very large and heavy Soviet 85mm gun barrel into Phu Khe's 5,000-foot elevation.

(603 pages.) - VOLUME V - 1964: Escalation and Military SARs

The year marked a substantial expansion of hostilities in Laos, and commencement of limited U.S. and Thai-Lao airpower. By early spring, the escalation, fostered by introduction of additional North Vietnamese troops into the country, skewed the tenuous balance of power between Asian adversaries.

The political situation came to an abrupt head in Laos when a rightist coup attempt exacerbated the shaky kingdom's woes almost to the breaking point, and created additional political instability within the Vientiane government. Quick to take advantage of the subsequent chaos, the communists, after capturing several important FAR and Meo sites, and creating thousands of additional refugees, made further gains. They forced government rightist FAR, and Kong Le, Commander of the Lao Neutralist FAN troops, completely off the Plain of Jars by mid-May.

Responding to a pressing requirement for current and accurate intelligence regarding enemy positions and movements, clandestine U.S. military involvement substantially increased with the reintroduction of in-country air reconnaissance missions within the Plain of Jars area, and along the eastern border (Panhandle) trails in central and southern Laos.

By mid-1964, the military balance of power between adversaries and the Lao situation appeared considerably more stable. However, this proved to be merely a mirage.

A hazardous place for aircraft, the Plain of Jars enemy lines of communication (LOCs) proliferated with sizable, well entrenched crew-served anti-aircraft gun emplacements. This was evident when a U.S. Navy reconnaissance pilot was shot down in an A-7 Crusader jet plane during early June, and Air America helicopter and fixed wing pilots participated in an unsuccessful SAR. Tight mission secrecy delayed the helicopter rescue attempt for several hours. Despite our efforts that resulted in battle damage to several aircraft, the man was captured. From that time on, the war continued to escalate.

Shortly afterward, another military pilot was shot down. Helicopter pilots rescued him the morning of the second day--a bittersweet accomplishment.

Because of perceived negative publicity and sensitivity to discovery of American air missions conducted in a supposedly neutral country, there was little or no realistic thought accorded by the powers-who-be to losing planes and men. Moreover, except for some pathetic equipment in the inventory, no viable military search and rescue (SAR) helicopter capability was in place at the commencement of the reconnaissance intelligence phase.

Therefore, largely by default, unarmed Air America civilian H-34 and fixed wing pilots, generally familiar with the area and available to assist, were pressed into service. At first, we did not mind, for we were present and, if at all possible, would never leave an American crew in the weeds to be captured. However, the duty soon became a bone of contention with our flight crews, for some of us were assigned SAR standby duty spending hours at strategic launch sites, with considerable loss of flight time. Although the USAF later developed a viable SAR capability, we were never completely off the hook to perform these missions, and continued participating and rescuing pilots throughout the entire war.

We began the SAR work on a catch-as-catch-can basis. There was always a narrow window of opportunity to implement a rescue. Therefore, if one was relatively close to a downed airman, he immediately converged on the scene and participated in the rescue attempt.

The initial policy was highly flawed. This was thrust to the forefront of operations when one of our helicopter pilots was shot down in August. He was rescued, but suffered a wound to his left foot, flash burns to his body, and developed psychological problems. His Filipino Flight Mechanic was killed.

Following that encounter, new standard SAR operating procedures (SOP) were developed and enacted. With crew survival in mind, the SOPs specified that fixed wing crews would first find and identify a downed pilot; that two pilots would man a helicopter cockpit; that a minimum of two helicopters would participate; and that armed A1E Skyraiders would accompany the flight. The method was successful. With the new procedures in place, and with more than a bit of luck, we did not lose another man.

By year's end, for the first time, major gains had been made and government forces controlled large parts of Military Region Two.

(903 pages.) - VOLUME VI - 1965: A Tedious Year

During 1965, United States Government (USG) leaders, instead of merely aiding the South Vietnam government to counter aggression from the North, conceived and implemented a difficult political decision to introduce U.S. Marine combat troops into the Southeast Asian conflict. Although overtly a neutral country, the fate of Laos depended on the ultimate outcome of the South Vietnamese conflict. This policy change, slowly evolving since middle 1964, greatly modified our operations.

In contrast to 1964, the first half of 1965 was liberally crammed with excitement for the Author.

Much of our increased combat activity related to a period of rapid Royal Lao Government (RLG) expansion throughout Laos. Threatened by actions in new areas close to the North Vietnamese border, and an ever-expanding U.S. air campaign in the North, the enemy struck back with a vengeance. This thrust was especially prevalent in Houa Phan Province (usually called Sam Neua Province) in northern Military Region Two, where we were obligated to relocate vast numbers of troops and refugees.

Supporting the huge expansion, additional H-34s, helicopter pilots, and flight mechanics were hired and assigned to our program. However, despite the supplementing entities, upcountry requirements demanded an even higher level of pilot hours.

As U.S. military Barrel Roll and Rolling Thunder bombing missions escalated in Laos and North Vietnam, formidable enemy anti-aircraft artillery defenses increased proportionally, as did the odds of U.S. aircraft losses. Since U.S. military SAR units were not yet wholly assembled, trained, or in place with adequate equipment and crewmembers, Air America's assets continued to be employed to perform perilous rescue missions never foreseen by management or the pilot force.

Because military losses generally occurred deep inside enemy territory, bona fide SAR rescue attempts became increasingly hazardous for those involved. Probing ever deeper northward, such operations culminated with the Author penetrating North Vietnam with other crewmembers to attempt what we erroneously believed was a single pilot rescue. The three-day episode resulted in one successful extraction, but at the expense of two badly battle damaged H-34s, and the life of a highly respected, irreplaceable Lao commander. As a result of this historic SAR, and a belief that SAR duty would continue to evolve into far worse situations, I danced on a very thin string, seriously doubting my survival and thinking of terminating my employment with Air America. Alleviating my stress and disconcerting thoughts of mortality, a great deal was attributable to my marriage to a lovely Thai lady.

USAF air rescue squadrons with vastly more efficient helicopters, equipment, and trained crews, eventually arrived in the fall of 1965 to partially relieve us of difficult SAR missions and to assume duties in the cross-border war. Except in Laos, we generally assumed a secondary role, as evidenced by the drastic reduction in our SAR requirements after July. If such a respite had not occurred, one could only speculate where military demands would have required us to venture next, or how many of us who elected to remain with Air America would have avoided the ultimate sacrifice, or the incipient ravages of stress and potential mental instability associated with such operations.

(963 pages.) - VOLUME VII - 1966: A Time of War and Peace

Although flowing into and mixing in the bubbling caldron of military action, each succeeding year in Laos proved unique, providing its own special mixture of challenge and excitement. Nineteen sixty-six was no exception. The hard-fought gains in Sam Neua Province were negated by the large Na Khang base's early loss and later efforts to retake the site. The operation resulted in the death of one of our youthful helicopter pilots, and nearly marked the Author's demise. Despite the initial problems, Na Khang was recovered, but it never resumed the breadth and status it had previously enjoyed.

The job's elevated risk was always a factor during any operation. However, this combat incident occurred so soon after our first son's birth, it caused me to pause and once again reevaluate my mortality and continued employment with the Company. It lent an air of increased conservatism to my future flying.

My family and I left Udorn on a planned, lengthy, and well needed home leave in the States, where I quickly recharged my batteries and forgot much of the disconcerting aspects of the Lao conflict.

In my absence, the war continued and substantial government military gains were made in Military Region One.

(566 pages.) - VOLUME VIII - 1967: More of the Same

Nineteen Sixty-Seven opened with a modicum of confidence within the war councils of the Western camp. None of this cautious optimism as related to Laos could have been possible without substantial and ever-escalating American airpower, which tended to equalize the countrywide balance of power--something the FAR could never have achieved on its own. Between four and five hundred U.S. aircraft were assigned and staged at seven Royal Thai Air Force Bases across the border in friendly Thailand. This mix of attack and support aircraft conducted varied missions: The slow-paced Rolling Thunder operation in North Vietnam, calculated to draw North Vietnamese representatives to the negotiating table; Barrel Roll in Military Region Two that attempted to slow the supply of goods to Pathet Lao and North Vietnamese Army forces in that critical region; and Steel Tiger in the ongoing interdiction of the central and southern Ho Chi Minh Trail systems. To some degree, bombing of enemy logistical supply lines in Laos and South Vietnam had hurt and disrupted the normal seasonal exchange of territory. The Pathet Lao and North Vietnamese failed to achieve previous dry season gains, but the long war continued.

For the first time in a half dozen years, in Military Region One, FAR tenuously held much of the agriculturally productive Nam Bac Valley, and a good portion of the region north of Luang Prabang. This successful operation helped plug traditional North Vietnamese invasion routes south from Dien Bien Phu along trails and the southern flowing Ou River, temporarily relieving pressure on the royal capital at Luang Prabang.

In important and strategic Military Region Two, there was reason for even greater optimism. After recapturing Na Khang in May 1966, General Vang Pao's mixed ethnic forces slowly regained and expanded strategic territory throughout upper Military Region Two. Moreover, his fighting men no longer appeared terrified of the ???dreaded nine-foot-tall??? North Vietnamese soldier. Competent road watchers along with Thai and Meo forward air guides (FAG) directed night air interdiction, primarily conducted by A-26 pilots, along main logistic arteries. The efforts tended to slow enemy supply vehicles and quell movement toward the strategic Plain of Jars, Moung Soui, and other points south.

In Military Region Three there was little large unit FAR ground activity. However, indigenous Special Guerrilla Unit (SGU) road watch teams continued to be trained by Agency Case Officers at outlying camps. These teams were dispatched to the far reaches of the Panhandle with the express purpose of accumulating viable trail-targeting intelligence to generate unabated and crippling bombing missions.

In Military Region Four, to the east of Pakse on the beautiful and strategic Bolovens Plateau, Agency (CIA) efforts accelerated to train and enlarge road watch teams to conduct intelligence targeting and aggressive action along the generically named, and increasingly important, Sihanouk Trail system.

Because of the war's seasonal tug-of-war and great numbers of extra-territorial enemy forces incountry, generally all who were involved in the conflict were aware that purported Lao Government successes and the lull in action were only temporary, and would not endure long.

Agency-sponsored indigenous road watch programs, tailored to gather intelligence for U.S. Air Force bombing strikes on the Ho Chi Minh Trail lines of communication system, greatly expanded throughout the southern portion of the country. Many teams had previously been trained for dual purposes that included both aggressive raids and ambushes. This training resulted in a change in United States Government policy that was tailored to increase pressure on North Vietnamese leaders to cease and desist their operations through aggressive measures against their lines of communications. Since the five Sikorsky USAF CH-3 Pony Express helicopters and their crews, staged at the rapidly growing USAF base at Nakhon Phanom, were multi-tasked to conduct missions in Thailand, Laos, and Vietnam, helicopter lift assets were limited for road watch operations. To fill this void, Air America personnel and H-34 helicopters were increasingly scheduled to participate and supplement Customer efforts in this activity.

Utilized in the past for casual road watch operations, Customers now deemed the UH-34D abundantly noisy and much too large a target for deeper penetrations into the Ho Chi Minh trail systems. Therefore, to increase the overall efficiency of large-scale delivery and retrieval of teams dictated by increasing Customer requirements, commercial type Bell turbine engine helicopters were obtained and placed in service by Air America at the Udorn base. Naturally, transition to the machines required re-training for us ???throttle twisters,??? who opted for the program. It also required a substantial adjustment in mind set for a completely different type of helicopter. At first, until sufficient assets were available, Bell crews complemented H-34 and USAF CH-3 helicopter crews. We then gravitated to missions entirely staffed with our own aircraft and people. This activity continued to increase and was highly successful.

(810 pages.) - VOLUME IX - 1968: Devastating Losses

This book includes the Author's perspective while flying 204/205 Bell helicopters, and combat experiences in a paramilitary role as a ???contract??? civilian pilot, who was covertly hired by the CIA to work for the quasi-government-owned company, Air America, Inc.

Although Special Guerrilla Unit (SGU) trail watch activity, tailored to generate strike targets and interdict enemy lines of communication (LOC) on the so-called Ho Chi Minh Trail system, proceeded at an elevated pace, there was an abundance of other ???normal??? work for helicopter crews in all five Lao Military Regions. These solo missions allowed the Author to become accustomed to the turbine engine Bell's numerous and significant differences as contrasted to the UH-34D "piston banger.??? This on-the-job-training, coupled with mountain flying techniques developed over years of difficult and hazardous flying in the country, was applied to the Bell. Although the Author initially experienced a challenging period while transitioning to the Bell, sufficient time elapsed whereby his thumb rule of ???armchair comfortable??? became a reality, and I became a reasonably safe and proficient Bell pilot.

Early in the year, with the advent of the massive North Vietnamese and Viet Cong TET offensive in South Vietnam, and increased enemy manpower and aggressiveness throughout Laos, the complexion and intensity of the conflict soared to new heights not previously witnessed in Southeast Asia. Abrogating the Royal Lao Government's slight balance of power gained through internal and external air superiority, the enemy's spring dry season offensive was unlike any in past years. The North Vietnamese Army exclusively initiated and controlled military action, and we lost substantial portions of territory.

Under this new enemy policy, the fighting portion of the communist Neo Lao Hak Sat (NLHS) political party, the indigenous Pathet Lao Army (PL), was mainly relegated to backseat support operations by their North Vietnamese mentors. Consequently, many strategic and important sites were overrun early in Military Region One and upper Military Region Two, resulting in a severe and unsustainable loss of government army troops, equipment, and morale.

Much of the enemy push to clear, reclaim, and control important lines of communication could be attributed to United States air power's diminution of the enemy's capability to fully exploit incountry logistic routes, and to the damage Rolling Thunder had inflicted on North Vietnam's infrastructure. Assisting this bombing program were electronic navigation TACAN facilities strategically positioned on high ground in north and south Laos that allowed air strikes to continue unabated despite adverse weather, when visual targeting was not feasible. Commencing with a December offensive against Moung Phalane's TACAN site, although they posed increasingly difficult goals, these sites became prime targets of the North Vietnamese Army in 1968, as the enemy employed elite sapper units (Dac Cong) and unique methods which will be described in the text.

Since the Southeast Asian war was becoming increasingly unpopular in the United States, with more vocal dissenters, another political motivation for enemy aggressiveness quite possibility included North Vietnamese leaders' anticipation of peace talks, and ensuing negotiations should USG agree to unilateral terms to cease bombing the North. The communist time-honored ploy of fighting and talking would then allow the enemy to push government forces from occupied territory back to the de facto demarcation line posited during the 1961 ceasefire and 1962 Geneva Accords on Laos. This imaginary line included half or more of the country, and most of the mountainous regions. If actually acknowledged, Laos' imaginary demarcation line would permit communist control of territory close to the 200-mile Ho Chi Minh/Sihanouk Trail supply lines. It would allow virtually unrestricted supply routes to all five military regions, and the ability to function with reduced RLG resistance.

Then under a pretext of Pathet Lao control and the fa??ade of Lao neutrality, continued aggression against South Vietnam, and an overriding quest to merge the North and South, could be more easily achieved. Deemed the most important, the USAF radar facility perched on the summit of Phou Pha Thi (Site-85) in Houa Phan (Sam Neua) Province assisted USAF jet sorties from the Udorn base to bomb North Vietnam targets with considerable accuracy.

The 1968 Vietnamese offensives in Sam Neua may have been a reaction to the gains and successes of General Vang Pao's guerrilla units. Interdiction and harassment by Meo units along routes leading from upper Military Region Two into the Ban Ban Valley, and ultimately to the Plain of Jars, were also seriously hampering the timetable of North Vietnamese leaders' goal of reuniting all of Vietnam under communist ideology. Intelligence gathered by crack tribal teams, trained to detect and direct air strikes on nighttime truck convoys and ammunition dumps, were severely impacting enemy logistic movement. Moreover, measures achieved in Sam Neua created such logistical problems that large numbers of enemy troops were required to keep the routes open.

(566 pages.) - VOLUME X - 1969: The First Plain of Jars

Each year of flying civilian paramilitary combat and supply missions in the theoretically neutral country of Laos for Air America, Inc. presented the Author with fresh interesting and exciting experiences, including numerous variables, and immensely challenging work, as any two situations were rarely equal.

A downside existed for a motivated aviator working in the Lao war zone. Because of geopolitical considerations that largely depended on resolution of the Vietnam conflict, the relatively unpublicized Lao conflict was generally considered a no-win situation by both the Royal Lao Government and the United States Government. For us in the trenches it was considered a pragmatic holding action and a buffer zone to allow the Thai government sufficient time to strengthen its military posture, and it represented an addendum to the overt war next door in South Vietnam. The Vientiane government hoped to remain relatively free until bilateral negotiations could provide a viable resolution. On the positive side, the effort in Laos tied up at least two North Vietnamese divisions from participating in the South Vietnam conflict.

The combination of a hostile environment and some minor battle damage were inherent in any job while flying in this highly fluid, low intensity conflict. Except in rare cases, the primary negative factor in the work revolved around the inability of the Lao Army to assume an aggressive stance and to strongly contest and sustain a winning posture against the home grown Pathet Lao and the dreaded North Vietnamese enemy. Although easy to rationalize, the lack of will to win still grated on some of us who had been trained and groomed by the U.S. Marine Corps, and who wholeheartedly believed that in war there was no substitute for victory.

There was no joy in Laos and little cause for optimism until an unexpected mid-year military reversal in Military Region Two, when the depressing military scenario surprisingly and radically reversed. Thanks to Military Region Two Commanding General Vang Pao's instinct and initiative, and to the efforts of his intrepid Meo warriors' wet season offensive and seizure of the strategic Plain of Jars, greatly facilitated by intensive United States and Royal Lao Air Force bombing. This action marked the first time in years that we had achieved a winning posture in lower Military Region Two. In accomplishing this, Vang Pao's original guerrilla war had morphed into a higher intensity conflict that eventually involved employment of and maneuvering of battalions and regiments.

As predicted by advisors, Vang Pao's successful campaign lasted only a few months. Nevertheless, work on the Plain afforded the Author a pleasurable flying experience that fostered a high degree of satisfaction and sense of accomplishment. Observing positive end results while flying supply and combat missions was enormous fun again. I never could obtain enough of it.

The North Vietnamese Army unquestionably possessed one of the world's most experienced and preeminent combat fighting forces. Considering the size and power of these forces, there was much skepticism that the diminished ranks of the Royal Lao Army, consisting mostly of Vang Pao's Meo in Military Region Two, could hold the vast Plain of Jars for an extended period, an assumption that eventually proved correct. But, owing to the USAF's prowess in delivering increased air power, and American civilian airborne supply vehicles, the Plain remained in friendly hands long enough for Vang Pao's men to discover, capture, or destroy vast quantities of military munitions, supplies, and other enemy implements of war. This extraordinary feat quite likely influenced Paris negotiations and convinced communist leaders to reset their projected timetable for their efforts to conquer Southeast Asia, and to install their brand of hegemony on the region. Moreover, the operation allowed Laos to remain a viable state for several more years.

Toward the latter part of the year Congressional hearings in Washington related to Laos revealed many facets of the previously furtive aspects of the war to the American public. In addition, the media, long thirsting for access to upcountry bases like that accorded in South Vietnam, was allowed limited passage north.

(669 pages.) - VOLUME XI - 1970: Continue to March

The Lao War has often been referred to as The Secret War. This might have been true to some degree, but only for the American people. The conflict was conducted during the ongoing Cold War, a period of highly strained relations and struggles for disparate ideologies between communist and Western nations. Although considered a misnomer in the Author's mind, with United States Government (USG) assent, there was method in allowing a civilian Central Intelligence Agency and its contract personnel to pursue a lengthy operation that sought to preserve the 1962 Geneva Accords on Laos, which specified that no foreign military should operate in Laos.

Of course, the North Vietnamese Army used a different tactic: communist leaders merely denied ever being in the country. Another reason for adopting a clandestine stance in Laos was the belief that disclosure of a close U.S. involvement and prosecution of a limited war would not generate negative world opinion in the event of Royal Lao Government defeats. A third motivation for maintaining a quiet, low key, war was a lack of sufficient American military assets to pursue yet another conflict in a mountainous, landlocked country containing few roads or other developed lines of communication.

As 1970 commenced, U.S. intelligence sources indicated that communist infiltration from the North into South Vietnam was increasing substantially. Additionally, the North Vietnamese Army had begun moving large numbers of troops and equipment into both Laos and Cambodia.

North Vietnamese leaders were intent on preserving their hold on, and expanding, what they considered a historical right to critical parts of Laos, particularly in the Plain of Jars region. Many Meo clans also considered the Plain of Jars region their titular homeland, although having emigrated from Yunnan, China, they had only lived there for a hundred years. The tribal people were tired of moving, and willing to take a stand, with our help. They were the principal warriors and defenders for the Royal Lao Government in that region.

Nineteen Seventy was to prove a difficult year for the Royal Lao Government, its military forces, and friends, as they attempted to preserve the kingdom. This was nowhere more prevalent than in Military Region Two, site of the 1969 successful Plain of Jars operation.

General Vang Pao controlled a group of indigenous T-28 pilots assigned to him. Unlike the restrictive rules of engagement, U.S. military air struggled under, there were no restrictions on Lao pilots regarding bombing missions. The watchword of the Meo pilots was to kill the enemy wherever he was located. Consequently, many of the pre-historic jars on the Plain of Jars from the Early Iron Age were destroyed???an unfortunate example of war's collateral damage.

Early in the year, the stress of combat flying was difficult for us helicopter pilots, who were called upon to support sites that were under pressure or in the process of falling to the communists, and to conduct major evacuations of both civilians and troops either relocating or fleeing encroaching enemy forces. Like all those involved in the operation had predicted, by February, RLG forces proved too few in number, and lacked sufficient motivation to defend the expansive Plain of Jars, or to repulse superior Vietnamese regular troops.

Thanks to the Allied air power advantage, the Plain of Jars had been held for a time during the first portion of the 1969-1970 dry season, but like a slightly bastardized version of Sir Isaac Newton's law of physics pertaining to a body in motion, when the massive North Vietnamese Army offensive commenced, short of employing nuclear weapons--B-52 Arc Light strikes were still not sanctioned in Military Region Two--there was absolutely no way of containing sustained enemy movement. By late February the Plain of Jars was once again in enemy hands, and we had lost our first Bell 205 helicopter--but not the crew--to enemy ground fire.

Despite attempts to impede them, the enemy advance continued. For the first time, they marched south until they reached the gates of Vang Pao's training and CIA-managed intelligence base at Long Tieng. It was only through the efforts of Special Guerrilla Units (SGU) from other military regions, regular Thai Army forces, allied tactical air, and the impending rainy season, that the base was preserved. During this period of hostility, we were not allowed to remain overnight at The Alternate, but commuted daily to and from Udorn to provide support.

Even as the enemy was rooted out and withdrew from the immediate perimeter of Long Tieng, for the first time during the long war, they never entirely departed the area. During months of hard fighting, Vang Pao's annual monsoon season offensive had placed harsh demands on us fatigued warriors, and had achieved limited objectives.

By year end, the military situation in Military Region Two was reasonably static, with front lines established about nineteen miles forward of Long Tieng, nearly the same distance as during previous years. However, the difference was that by the close of the official wet season, pockets of well-supplied enemy units remained in position further west than during any previous year. Contrary to normal seasonal standard operation procedures, they had not departed the field during the rainy season to rest and refit in North Vietnam. They were well supplied and in position to renew a dry season offensive against Long Tieng and other government positions.

During a year beset with many firsts, in the spring a political and military upheaval in Cambodia had ousted the premier, and caused the closure of a major logistical port vital to North Vietnamese interests supplying the war effort in South Vietnam. This turn of events compelled North Vietnamese construction teams and infantry to push their supply lines further west toward population centers in southern Laos. During the process, they seized the provincial towns of Attopeu and Saravane, and the southeast portion of the Bolovens Plateau was hotly contested. By year's end the enemy had captured most of the territory in Military Region Four deemed necessary to ensure unimpeded access to their lines of communication along both ground and water routes.

(632 pages.) - VOLUME XII - 1971: The Second and Final Plain of Jars

The 1971 period commenced with communist forces intent on continuing to reestablish and improve their supply lines through Laos into South Vietnam in order to implement the North's aims to reunite Vietnam and impose their leaders' ideology on the region.

Having conducted inroads deep into Laos' Military Region Two's central region encompassing the strategic Plain of Jars, and remaining in place where Meo tribal leader Major General Vang Pao's forces were attempting to hold territory, the enemy, as expected, was poised to resume a major offensive on the important base at Long Tieng (Lima Site 20A). General Vang Pao's defenses, constructed in depth around the coexisting sites of Sam Tong and Long Tieng, were manned by several infantry battalions, including Meo, Special Guerrilla Units (SGU) seconded from other military regions, and volunteer Royal Thai Army troops, which included supporting artillery battalions. However anemic, to prevent end runs on the base, the government defense line extended east from Padong (LS-05) to the west at Moung Soui (L-108) and beyond that to the Khan River, a demarcation line that separated Xieng Khouang and Luang Prabang Provinces. Artillery firebases (FSB) established to support the immediate area were positioned north on Skyline Ridge overlooking the Long Tieng Valley, further north in the Sam Tong bowl, and at Ban Na (LS-15), and at the Romeo Ridge south of Tha Tam Bleung (LS-72).

Prodded into action, military leaders in other regions, particularly in the southern provinces, were preparing to counter enemy gains and reclaim lost territory. A massive cross-border operation planned to interdict the Route-9 Panhandle area east of Savannakhet from South Vietnam was imminent. Pressured by the Nixon Administration to test the effectiveness of U.S. Government's (USG) Vietnamization policy, the South Vietnamese government's goal was the capture of the communist logistical crossroad in the Tchepone Valley.

If the 1969-71 dry season was any indication of impending events, then 1971 was shaping up as a battle royal in Military Region Two.

During one of Vang Pao's standard diversionary operations, his mobile troops moved to the eastern periphery hills of the Plain of Jars and then back onto the plateau. By summer, half the Plain of Jars was back in government hands in preparation for commencement of the Second PDJ campaign. During July, interlocking artillery fire support bases were rapidly established and manned by Thai volunteers. After completion, the formidable defenses in depth were believed to be impenetrable.

The communists were undeterred. By late fall, the enemy increased pressure on the Thai bases. Then, introducing heavy 130mm Soviet field artillery guns that could outdistance any of our weapons and tanks, for the first time, they systematically reduced each fire base. By the third week of December, we had lost the Plain of Jars. During the confusion and fracas, the Author was shot down in a S58-T, a twin-engine turbine Sikorsky helicopter, one of five machines the Udorn maintenance department had assembled.

(744 pages.) - VOLUME XIII - 1972: A New and Invigorating Program

The year's start appeared grim. Supported by a number of 130mm field canons that far outranged any of our artillery guns, and commanded by experienced and successful leaders, North Vietnamese battalions and divisional regiments were poised before the collapsing gates of Sam Tong and Long Tieng. For the Royal Lao Government and the long-suffering warriors involved, the situation amounted to a struggle for survival. The Long Tieng base and its long, colorful history had always represented a primary obstacle to the North Vietnamese Army attempts to discourage the RLG and Major General Vang Pao's Meo soldiers from continuing their long war of attrition. Fortunately, the base defenders held, and with the advent of the annual wet season, the enemy withdrew.

It was a year that marked the Author's transition from a helicopter line and S-58T instructor pilot to participation in the highly secret Special Project program administered by the AB-1 Agency (CIA) department, and was designed to conduct long range indigenous team insertions and clandestine intelligence gathering missions deep into enemy territory. The ambitious night flying program kept the Author off the front lines in Military Region Two, but presented other more dangerous and extremely challenging situations with which to cope. Although we had two pilots in the cockpit, two aircraft, and were equipped with automatic weapons, we no longer enjoyed the benefit of armed military fixed wing assets to escort us on missions. In addition to conducting a first-time mission into Cambodia, the program involved learning the intricacies of newly developed special navigation, night vision, and weapons recognition equipment. Despite problems, failures, and a few successes involved in the enterprise, I became addicted to the work, and continued in the program throughout my remaining tenure with Air America.

(682 pages.) - VOLUME XIV - 1973: Holding on During Negotiations

With geopolitics and the military balance of power dramatically changing in Southeast Asia, January commenced with the general expectation of a successful ceasefire agreement in Paris between the United States Government and North Vietnam that would act as a catalyst and precursor to a similar agreement for the Kingdom of Laos. In anticipation of such an agreement, both the Royal Lao Government and Democratic Vietnamese Republic (DVR) leaders earnestly sought to capture and control select territory that might be employed as future bargaining chips during ongoing negotiations between the communist Neo Lao Hak Sat (NLHS) and government officials in the administrative capital of Vientiane.

For the Royal Lao Government and long-suffering Royal Lao Army, Meo, Kha, and other tribal warriors involved in the conflict, the situation still entailed a consuming struggle for survival. Continuing their prolonged war of attrition, the Lao Army and Major General Vang Pao's Meo soldiers, aided by troops from other military regions, and Thai ???volunteers,??? were the primary obstacle to the North Vietnamese army's designs on Military Region Two.

The New Year also marked the Author's continued and expanded participation in the Special Project, the AB-1 Agency supported, funded, and administered intelligence gathering program. The extremely challenging night work was designed to implement clandestine intelligence gathering by employing electronic devices conceived and developed at the CIA's Langley, Virginia, high-technology laboratory. Newly instituted, the devices used and the difficult work included James Bond type gadgets and innovative methods that included stranger-than-fiction stimulating night missions. For those of us in the trenches, the program required total dedication, concentration, and a high level of proficiency from its minute number of participants. Agency missions kept the Author away from the still hazardous front lines, but as the clandestine work entailed penetrating deep into enemy territory, it presented entirely new dangerous and exceptionally challenging situations.

In addition to the ongoing war that had lately eliminated so many of our fine employees, for members of the pilot group in the previously formed Far East Pilot Association (FEPA), the year commenced without a new work agreement. Paramount to the continued operation, our jobs and livelihood would depend on the outcome of contentious bargaining and negotiations with the Company.

- VOLUME XV - 1974: Out of Business in Laos

My twelfth and final year with the Air America, Inc. Company commenced with the knowledge that shortly after a bilateral coalition government was formed in Laos, as specified in the ceasefire agreement of February 1972, Air America would be out of business in Laos.

Like the Hundred Years War in Europe, there were times in earlier years when I believed our ???piss-poor-war??? that had morphed into a full-scale conflict would continue forever. I half-seriously speculated that after we had defeated the communists in Southeast Asia, Air America would be assigned to conduct reconstruction work throughout Vietnam, and my two sons would eventually continue my work. Of course, like ???castles in the air,??? this proved nothing but a pipedream.

On a positive note, we had been informed earlier by Agency types that Special Project intelligence work would continue for at least another year. Because of the Nixon Administration Watergate scandal or other factors to which I was not privy, this projection failed to materialize. Consequently, after more than a decade with the Company, I was left at odds looking for a suitable job. There was continued flying available in South Vietnam, but not familiar with the region, I rejected this offer. Fortunately, other overseas helicopter work at reasonable wages and good living conditions for families was still available. I ended up working as an instructor pilot for Bell Helicopter International at Isfahan in the Middle Eastern country of Iran, but that is a subject for another interesting and colorful story, set in a very different and tumultuous period of history.

The short 1974 book represents the culmination of our participation as civilian crewmembers conducting paramilitary missions for the CIA and implementing United States Government policy. Gone were the colorful days of combat and challenging Special Project intelligence gathering missions. Emphasis was now centered on clean-up work in preparation to leaving the Laotians--mostly the Meo people--to their own designs. No one considered the decision to leave the Lao to be America's finest hour.

As history recorded, in 1975, Laos and then South Vietnam succumbed to the communists. As some indicated, we had won the battles in South Vietnam, but had lost the war.

Vietnam Center & Sam Johnson Vietnam Archive

-

Address

Texas Tech University, Box 41041, Lubbock, TX 79409 -

Phone

806.742.9010 -

Email

vnca@ttu.edu