The Women of the Vietnam War: The Aftermath

APS-71-796 Vietnam The Army Nurse in Vietnam Cpt. Theora L. Peyton (Arlington, VA), changes an intravenous saline bottle on a patient at the 3rd Field Hospital. 12 July 1971 Photo by SP5 Logan McMinn USA Sp Photo Det, Pac fn

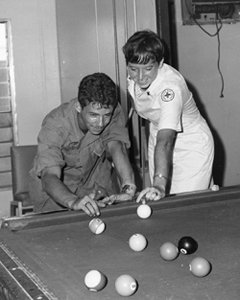

"Put on some perfume, lipstick, and a smile." Although this was the basic mantra that the women who served and volunteered in Vietnam were instructed to follow, it was more often than not a difficult burden to bear. Many nurses and American Red Cross Recreation workers, also known as "Donut Dollies," held this mantra near and dear while, at the same time, struggling to maintain composure and a perky smile on their attention drawing American faces. Although it seems that overall, the Donut Dollies had much better experiences while entertaining the deployed American soldiers and were able to leave Vietnam and return to their lives with fewer negative repercussions, they too were overworked and overtired like Army, Air Force and Navy nurses. On top of this, nurses were often forced to become emotionally numb, which stemmed from juggling demanding patient care, which increasingly entailed more physician level work, offering kind words and soft, caring hands, and little to no free time away from their places of work to decompress. When precious downtime was allotted, it often became oppressive as many soldiers looked to any American women as companions, including nurses. Because of this, nurses began to keep to themselves during downtime. One Vietnam nurse states that her supervisor once told her to not "go around looking worried and horrified…The guys need all the care and hope they can get." This begs the question, "who will offer comfort to these women?" While this statement holds much truth, it also reveals a harsh reality about the lives of nurses, as well as Donut Dollies, during their year in Vietnam and how it would later affect their lives back in the United States.

The Harsh Realities of Women's Lives While Serving in Vietnam

The average age of a Donut Dolly was 21, and many Army, Air Force and Navy nurses were 23. In turn, the average age of the American soldiers deployed in Vietnam was 19. While the majority of the women serving and volunteering in Vietnam arrived excited and willing to give their all, they soon became drained as their jobs consumed their entire days. Vietnam was a different type of war that American troops had not seen before, there was no specified front line and battle could erupt anywhere. These women were on guard 24 hours a day, seven days a week. Although much later after the war it was concluded that male Vietnam veterans suffered from Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), women were not acknowledged as having this until fairly recently. It seems impossible to believe that anyone living through what Army nurse Helen White experienced on an almost daily basis for one year could not leave the war zone without PTSD.

"As I open the door, the smells hit me first. The smells are of fresh blood, old blood, rotting human flesh, body fluids, disinfectants, iodine, drainage from various infections and God knows what else. Men are strung up in all kinds of traction, some have bulky splints or dressings and a few have casts of all kinds. Pieces of them are missing."

Other nurses have similar stories and memories, which still haunt them to this day. Although this was not a combat situation, it was highly stressful and these women were often not properly prepared for the sights and sounds of heavy combat. With such a young military force and a high number of casualties and severely wounded soldiers, morale was low for these women; yet they were forced to be the caregivers and smile, even when all they wanted to do was cry. If any emotion was close to coming to the surface, a woman was expected to leave for a moment to collect her thoughts and return both polished and ready to begin again. Sharon Cummings, a Donut Dolly from April 1966 – April 1967, describes how she would always smile, no matter how she felt: "it got harder and harder to greet all the new guys - many of whom I knew would not make it back to the States alive. I would still be brave and smile every day…" Both nurses and Donut Dollies all felt as though they were part of a team that needed to be strong and nurturing amid the battles and jungles of a relentless war zone. It was this sense of partnership that kept the women of the Vietnam War working 12 – 15 hour days and giving all American soldiers the necessary amount of attention.

- The Forgotten Veterans (source unknown, undated) (full record)

- Heroines of Healing, by Col. Henry J. Pratt (Army Reserve Magazine Vol. 39, No. 4, Winder 1993/94) (full record)

- Book: "Angels in Vietnam: Women Who Served," by Jan Hornung; Call Number: DS559.8.W6 A5 2002

Women Do Not Suffer from PTSD Because Good Girls Did Not Go To War

This Australian nurse is among about 400 foreign medical personnel working in South Vietnamese hospitals. Here Josephine Champion of Melbourne makes a surgical case more comfortable in the Bien Hoa provincial hospital (undated)

PTSD was not formally recognized as a mental disorder until 1980, yet it was not until 1992 that women were also accepted as having the disorder and offered their own places for recovery, where all female patients were treated. Prior to the 1980’s PTSD was often referred to as "shell shock," "combat neurosis," "feigning illness" or "combat exhaustion." PTSD is essentially chronic and/or delayed depression which is manifested in several ways: preferred self isolation, uncontrollable rage, avoidance of feelings and alienation from friends, spouses and family, anxiety, survival guilt, sleep disturbance and nightmares and intrusive thoughts. Not all who are diagnosed with PTSD will exhibit all of the above symptoms, and symptoms will be varied from person to person. Unlike the typical male who suffers from PTSD, the typical female will be highly successful, often earning one or two graduate degrees and holding prestigious jobs. However these things are accomplished to fend off depression, anxiety, suicidal thoughts and sleepless nights as it was normally not accepted for a woman to outwardly express rage. It was a common belief that "good girls don’t go to war," which caused many women veterans to not talk about their service, even to employers, spouses and family members. Many suffer from guilt as well, however it is because they feel that they could have contributed more, even though they did all that they could.

- Lipstick and a Smile: Story of One Nam Nurse, by Helen White (2003) (full record)

- The Nurses of Vietnam, Still Wounded, by Laura Palmer (The New York Times Magazine, November 7, 1993) (full record)

Recognition and Remembrance

In 1984 a former Army nurse who served in Vietnam, Diane Carlson Evans, began work to appropriately honor all women Vietnam veterans. In October of 1988 her work came to fruition as legislation signed by President Reagan authorizing the Vietnam Women’s Memorial Project to erect a monument on Federal land was unanimously approved by Congress. Then on November 11, 1993, Veterans Day, women veterans were finally honored for their dedication and skill during the Vietnam War. The Vietnam Women’s Memorial was dedicated on this day in Washington, D.C. in the presence of a large crowd for both women and men. The bronze statue was erected near the Wall, a memorial with the names of over 58,000 Americans who perished during the war, eight of which are women. The statue was created by the famous Glenna Goodacre and depicts three female nurses in fatigues. One nurse looks to the sky in search of a medevac helicopter, another cradles a wounded male soldier and the third nurse kneels in shock, realizing the horrors of the war.

- Program of the Dedication of the Vietnam Women's Memorial - November 11, 1993 (full record)

- Vietnam Women's Memorial Project button

Vietnam Center & Sam Johnson Vietnam Archive

-

Address

Texas Tech University, Box 41041, Lubbock, TX 79409 -

Phone

806.742.9010 -

Email

vnca@ttu.edu